At the cross, where I first saw the light

including

Take Me Home

Once I was bound a slave to sin

When my heart was so hard

O Jesus, Lord, thy dying love

Alas! and did my Saviour bleed

with

HUDSON

I. Origins: Take Me Home

The gospel-campmeeting refrain “At the cross, at the cross, where I first saw the light” traces its history to the song “Take Me Home,” written by W.L. Bloomfield, “and sung by Edwin P. Christy at Christy’s American Opera House, NY” (NY: Firth, Pond & Co., 1853 | Fig. 1). The words to the song begin “Take me home to the place where I first saw the light, to the sweet sunny south take me home.” The music of this edition is not the same as the gospel refrain, but the words are foundational to the refrain’s origins.

Fig. 1. W.L. Bloomfield, “Take Me Home” (NY: Firth, Pond & Co., 1853). Digitized from a copy at the University of Michigan.

William Leach Bloomfield (born 1812 in Tiverton, England; died 21 Apr. 1864 in Brooklyn, NY) was known for several years (as early as 1838, retiring in 1860), as a composer of polkas for band and as the director of the military band at the Fort Columbus military base on Governors Island in New York Harbor. An official website for the island described the early history of musical training there:

The new School of Practice for U.S.A. Field Musicians opened on Governors Island in the 1830s. The school trained musicians in fife and drum, adding bugle after the Civil War. Between fifty and ninety students, initially quartered in the casements of the South Battery, attended the school at one time. They were known as the Music Boys, an apt nickname for a group that skewed young; in 1860, two-thirds of the 60 Music Boys were between the ages of 13 and 16. Field musicians would perform multiple times each day, performing bugle calls like reveille in the morning and retreat in the evening, as well as at daily dress parades. The army band would also play at ceremonial occasions, like welcoming visiting dignitaries, at military funerals, and at the Island’s esteemed garden parties.[1]

Hermann L. Schreiner (born 21 Jan. 1832 in Hildburghausen, Saxe-Meiningen, Germany; died 5 September 1891 in Gera, near Leipzig, Germany) emigrated to the United States in 1849 and lived for a time in Wilmington, North Carolina. Hermann published one of his first songs, “Louise Grand Waltz,” through P.K. Weizel in New York in 1853. Around the same time, his parents arrived from Germany, and they all settled in Macon, Georgia, where Hermann and his father Johann (John) C. Schreiner (1806–1870) founded their own music store and publishing company, J.C. Schreiner & Son. They purchased another storefront in Savannah in 1862, and Hermann moved there while his parents remained in Macon. Some of Hermann’s songs in the 1860s were distributed through other publishers, including Blackmar & Bro. in Augusta, Georgia. Hermann wrote new music for Bloomfield’s song “Take Me Home” and published it through his own company in 1864 (Fig. 2), without crediting Bloomfield. Hermann’s tune is clearly recognizable as the foundation for the later camp-meeting refrain “At the cross.”

Fig. 2. Hermann L. Schreiner, “Take Me Home” (Macon: J.C. Schreiner, 1864).

Also living in Georgia at the time, 1863–1865, was John Hill Hewitt (1801–1890), an itinerant poet, playwright, and composer, sometimes known as the “Bard of the Confederacy.” Hewitt and Schreiner wrote a song together called “When upon the field of glory: An answer to ‘When this cruel war is over,’” words by Hewitt and music by Schreiner, published through the J.C. Schreiner company in 1864. Schneider published several of Hewitt’s songs in 1863 and 1864, but starting in 1864, Hewitt sent songs to other publishers under his pseudonym Eugene Raymond. Most notably, he sent his own version of “Take Me Home” to Blackmar & Bro. in Augusta. This appeared in a “Southern Edition” in 1864, “Re-arranged for the Piano Forte” (Fig. 3). The melody in this edition was nearly identical to Schreiner’s edition, but neither Bloomfield nor Schreiner were credited.

Fig. 3. Eugene Raymond [John Hill Hewitt], “Take Me Home” (Augusta, GA: Blackmar & Bro., 1864). Digitized by the Library of Congress.

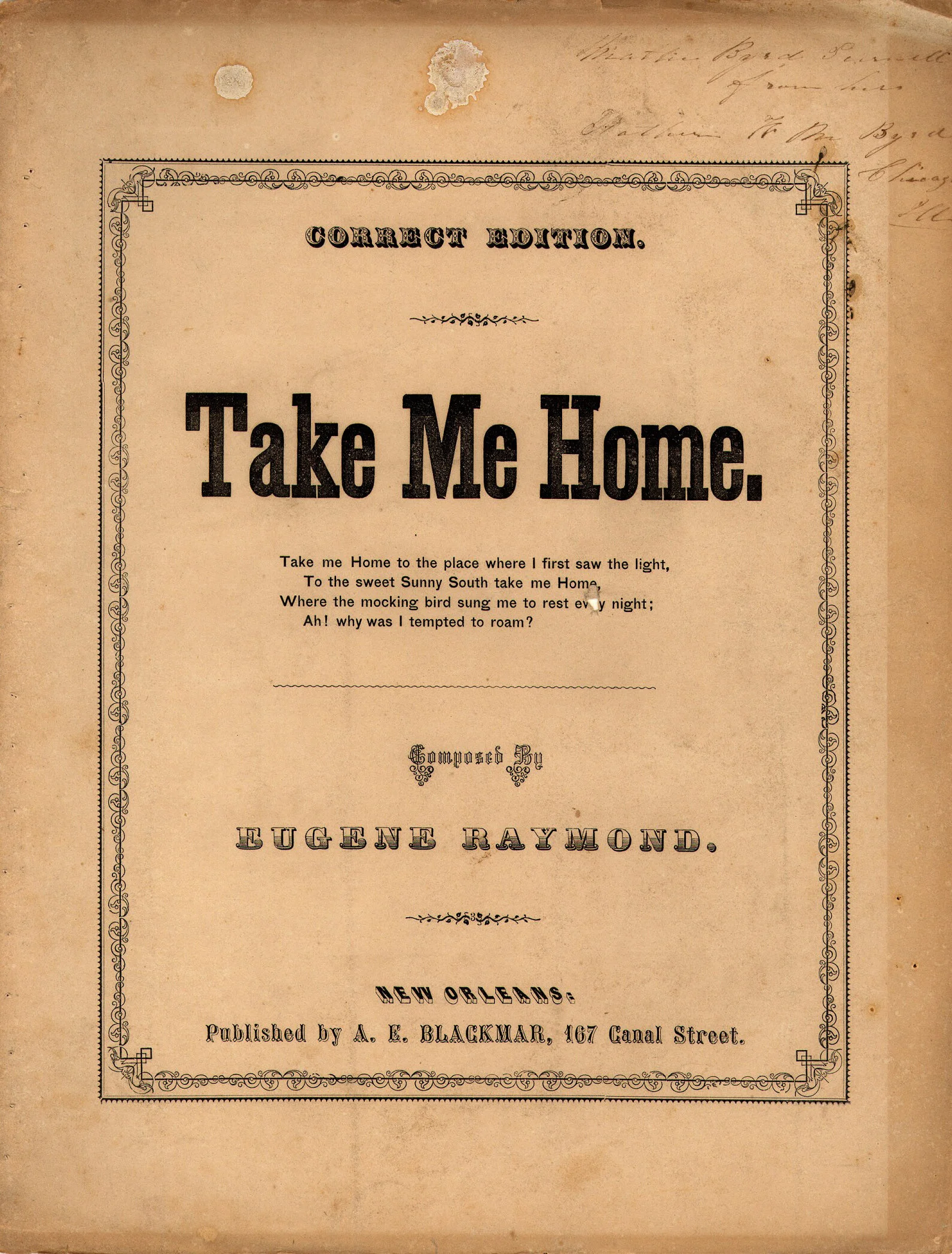

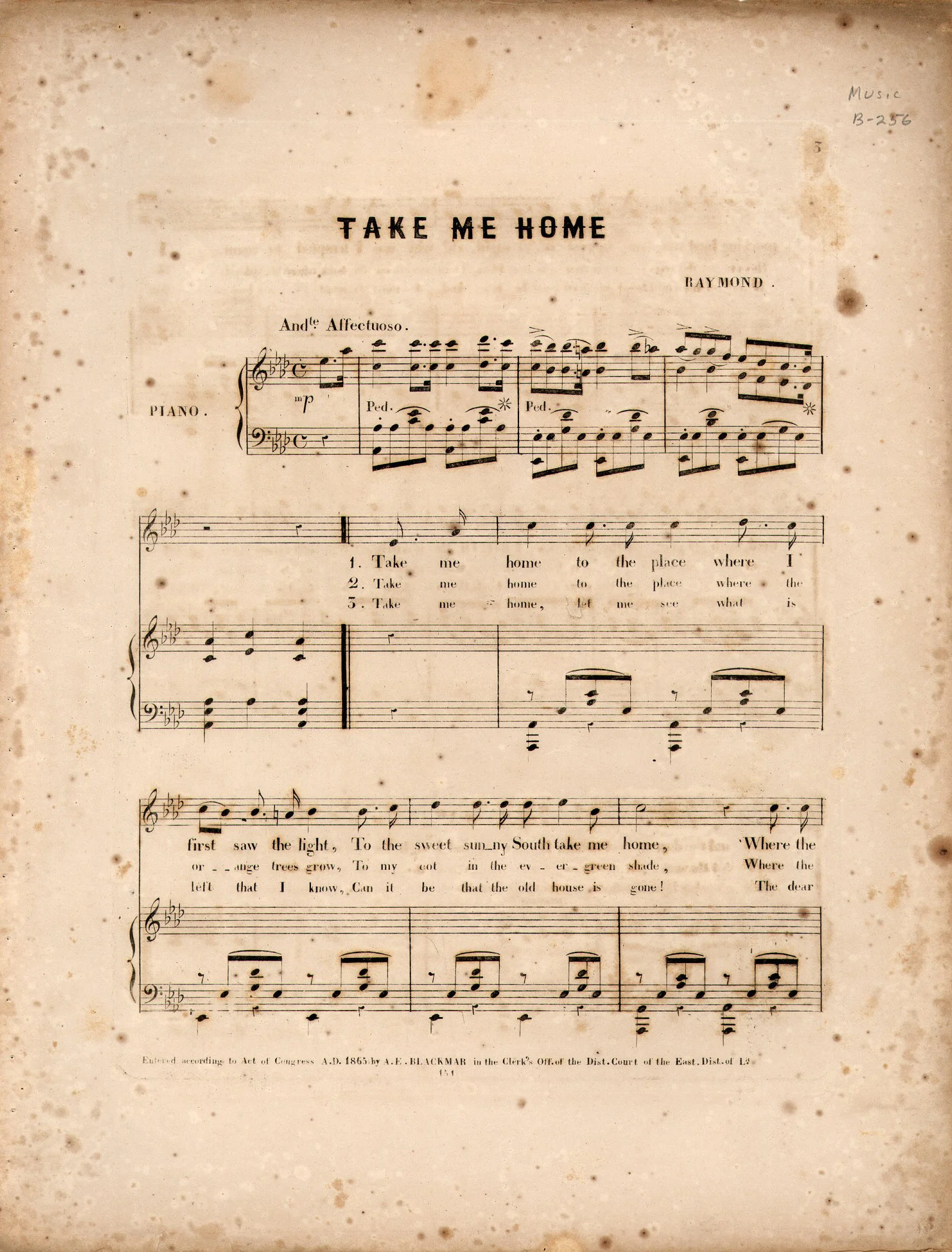

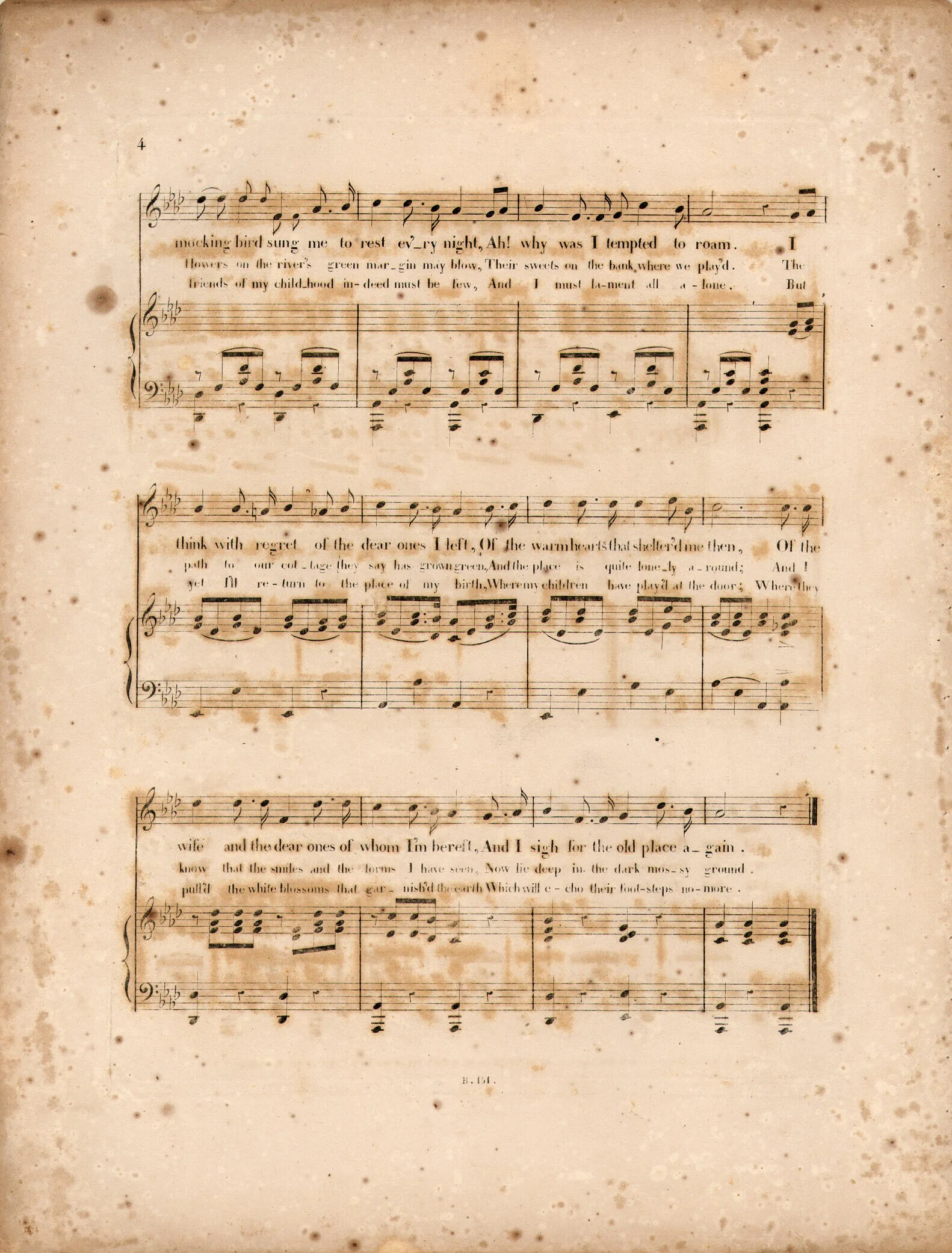

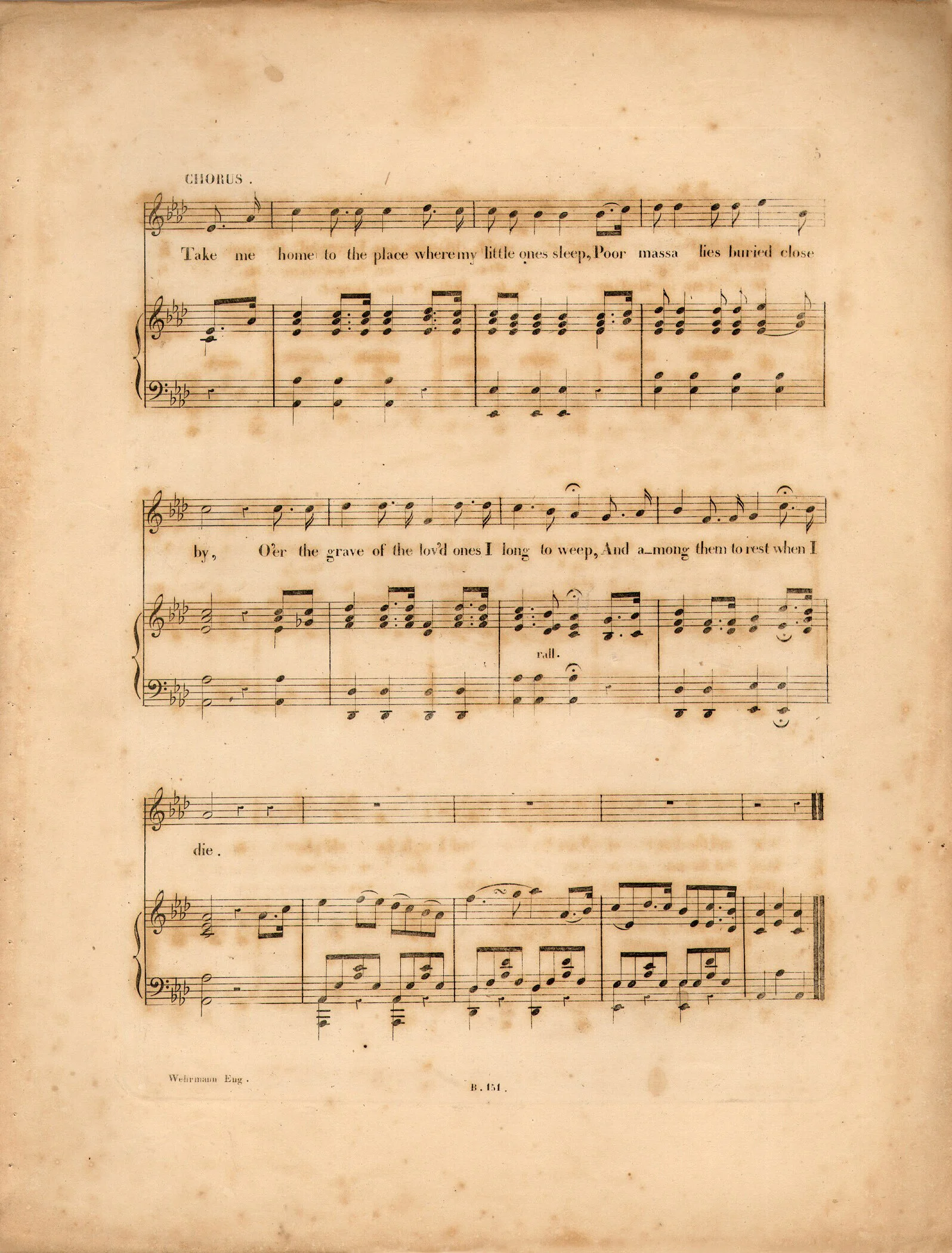

Another edition, the “Correct Edition,” appeared in 1865, this one “Composed by Eugene Raymond,” published by A.E. Blackmar in New Orleans, with changes to the melody and the accompaniment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Eugene Raymond [John Hill Hewitt], “Take Me Home” (New Orleans: A.E. Blackmar, 1865). Digitized by Duke University.

On 10 April 1865, one day after the surrender of General Lee, Hewitt bought the Augusta office of Blackmar & Bro. and published some songs under his own imprint, but in the midst of a devastated post-war southern economy, he lost a lot of money in a short amount of time and moved back to Baltimore to find work there.[2] The Schreiners continued to operate their business, consolidating in Savannah after the death of John Schreiner in 1870. A notice of Hermann’s death in 1891 said “grit and determination were two of his chief qualities.”[3]

Does the melody of this song belong to Hermann L. Schreiner or John Hill Hewitt? The circumstances of the situation are difficult to determine, but given Hewitt’s short-lived professional relationship with Schreiner, the avoidance of using his own name when he published songs through Blackmar, and the initial claim of his 1864 version of “Take Me Home” being “re-arranged for the piano forte,” the credit for the tune most likely lies with Schreiner.

II. At the Cross

A. The Salvation Army, England

The opening words of “Take me home to the place where I first saw the light” were turned into a Christian parody, “At the cross, at the cross, where I first saw the light,” emerging in England early in the 1880s, especially among workers of the Salvation Army, quite possibly devised by one of their leaders.

The earliest known reference to the Christianized refrain appeared in The Luton Reporter, 28 April 1883, describing a meeting of the Salvation Army in Luton, Bedfordshire, England, on 25 April 1883, led by General William Booth (1829–1912):

In place of a regular speech, they were to hear the champion prize-fighter from Yorkshire—if any person did not believe he (“Big Ben”) had been a prize-fighter, let him step forward and invite him to a round (laughter). “Big Ben,” who wore a white guernsey with the words “Salvation Army” embroidered thereupon, whose accent betrayed the north countryman, and who made a pleasant impression upon the audience by the unaffected simplicity of his manner, then stepped forward. He sang a solo beginning,

At the cross, at the cross, when I first saw the light,

And the burden of my heart rolled away,

It was there by faith I received my sight,

And now I rejoice night and day.

These words were to a “nice tune,” as the singer pleasantly observed, and the strain was heartily taken up by the audience.[4]

The words of the refrain bear a resemblance to an earlier gospel song, “I left it all with Jesus long ago” by Ellen H. Willis, first published in 1871, especially the first stanza, which says, “When by faith I saw him on the tree,” and “From my heart the burden rolled away.” The unknown person responsible for Christianizing the refrain could have been inspired in part by Willis’s song; it was included in Salvation Army songbooks before 1883.

Just a couple of months later, the refrain appeared together with a new text, “Once I was bound a slave to sin,” by Captain [Albert] Hadden of the Salvation Army, in The War Cry, 23 June 1883 (Fig. 5), in seven stanzas. In this example, it seems as though the refrain was already familiar to readers—meaning Hadden does not appear to be responsible for Christianizing “Take Me Home”—and the refrain ended “now I rejoice night and day.” Hadden’s text was met with little interest and has not been reproduced in other collections.

Fig. 5. The War Cry, 23 June 1883. Image courtesy of Salvation Army International Heritage Centre, London.

Another early account of the refrain was described in an article in the Western Mail (Cardiff, Wales), Thursday 27 September 1883, p. 3:

On Wednesday morning at an early hour the Salvationists who had been imprisoned at Cardiff on their persistent refusal to pay fines of 2s. 6d. and costs for obstructing the thoroughfare at Trealaw were set at liberty. . . . In the afternoon the released Salvationists took train for Trealaw, where it was expected a “hallelujah flare up” awaited them. . . . As soon as they were seated in the train all the members of the Army, dressed in their particular costumes, commenced singing:

At the cross where I first saw the light,

And the burden of my heart rolled away,

’Twas there by faith I received my sight,

And now I am happy all the day.

Herbert H. Booth (1862–1926), fifth child of General William Booth, was given charge of the Army’s music department at Clapton from 1883 to 1888, thereafter becoming head of Army work in Britain. He wrote many hymns, including a set of stanzas to accompany the gospel refrain. “When my heart was so hard” was printed in the anniversary report of Salvation Army work in Scotland, August 1882–August 1883, text only, then in Salvation Music, Vol. 2 (London: Salvation Army, December 1883 | Fig. 6) with the tune. Booth’s new stanzas were intended to follow the same melody as the refrain, and he incorporated the idea of seeing the light into his text. Notice also how the refrain ended “now I am happy night and day.”

Fig. 6. Salvation Music, Vol. 2 (London: Salvation Army, December 1883).

B. Salvation Army, United States

The refrain was transmitted to the United States by members of the Salvation Army. The earliest known example was documented in The Weekly Bee (Sacramento, CA), 19 September 1884, describing an event on 15 September 1884. The article attests to the song’s roots in “Take Me Home”:

The corps of the army which is here consists of Major Wells, a woman about 25 years of age, who is the wife of the commander of the Salvation Army on the Pacific coast. Both Mr. and Mrs. Wells are Majors in the organization, and the former is now wrestling with the devil in sinful San Francisco. . . . At the conclusion of the Major’s remarks, song books were distributed, and the audience joined in singing a hymn to the tune of “Take me back to my home in my own sunny south.” The chorus ran as follows:

At the cross, at the cross,

Where I first saw the light,

And the burden of my heart blew away,

It was there by faith I received my light,

And now I am happy night and day.

The refrain was adopted into American songbooks the following year, in 1885. The first published arrangement was by Edward E. Nickerson (1834–1899), who had joined the Salvation Army in July 1884 in Lynn, Massachusetts. He compiled three collections of Highway Songs (Nos. 1–3, 1885–1887); the refrain “At the cross” was included in the first collection, set with two stanzas from “There is a fountain filled with blood” by William Cowper (Fig. 7). His version was labeled “Sung by Alice Terrell,” and the last line of the refrain used the phrase “happy night and day.”

Fig. 7. Highway Songs [Nos. 1 & 2] (Boston: E.E. Nickerson, 1886).

Nickerson’s arrangement was used as the basis for a version by R. Kelso Carter (1849–1948), a Methodist preacher who was active in camp meetings and revivals. Carter wrote a new text for the tune, beginning “O Jesus, Lord, thy dying love,” published in Precious Hymns for Times of Refreshing and Revival (Philadelphia: J.J. Hood, 1885 | Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Precious Hymns for Times of Refreshing and Revival (Philadelphia: J.J. Hood, 1885).

As a matter of curiosity, the collection Precious Hymns was dated 1885 on the title page and in the copyright notice, but this song was dated 1886. A similar discrepancy can be seen in Gems of Gospel Song, also published by Hood, containing “O Jesus, Lord, thy dying love” and dated 1885, while at the same time containing cross references to a collection published in 1886 (The Temple Trio).

Another early example demonstrating Nickerson’s influence is found in Glad Hallelujahs (1887), compiled by John Sweney & William Kirkpatrick, where the refrain “At the Cross” was used with the hymn “O how happy are they” by Charles Wesley, music arranged by E.E. Nickerson (Fig. 9). In this example, the refrain ends “happy all the day.”

Fig. 9. Glad Hallelujahs (Philadelphia: Thomas T. Tasker Sr., 1887).

C. Ralph Hudson Tune

In the United States, the cross refrain is most commonly associated with the setting by Ralph Hudson (1843–1901). In the 1880s, Hudson was a composer-publisher living in Alliance, Ohio, and he was active as an evangelist, licensed to preach in the Methodist Episcopal Church. He published the refrain in his songbook Songs of Peace, Love, and Joy (1885 | Fig. 10), using a text by Isaac Watts, “Alas! and did my Saviour bleed.” In the other examples above, the common approach was to use the same melody for the stanzas as for the refrain. Hudson’s version was unique in the way he created a new melody for the stanzas, thus giving the song a proper verse-chorus musical structure. His version of the refrain ended “happy all the day.”

Fig. 10. Songs of Peace, Love, and Joy (Alliance, OH: R.E. Hudson, 1885).

How did Hudson become acquainted with the gospel refrain? Like the other examples above, the answer still possibly lies within the Salvation Army. In the 1880s, the Salvation Army was making its presence known in northern Ohio. On 12 June 1884, one Ohio newspaper reported:

Twenty-four men and women of the Salvation Army arrested in Cleveland, Ohio, for disturbing the peace by parading, singing, shouting, and praying aloud, were fined small sums. Twenty of the accused refused to pay the fine and were released on bail.[5]

Closer to where Hudson lived in Alliance, the Salvation Army opened a meeting hall in Akron later that summer:

THE SALVATION ARMY COMING: Two members of the Salvation Army, dressed in blue suits, with red shirt fronts and caps on which were the words “All for Jesus,” reached this city Wednesday. The object of their visit was to hire a hall and make arrangements for the coming of the Army, which will appear here about August 1st, if a hall can be secured and satisfactory arrangements made. These representatives also called on several ministers, who say that while they will not encourage the work, yet they will not oppose it.[6]

Later that fall, operations were in full swing in Akron:

The Salvation Army is still holding forth at The Union, besides having nightly meetings upon the streets. They have made over 70 converts since “opening fire” in Akron. They have been recently reinforced by Capt. Mollie Wright and Lieut. Jennie Fellows, from Alleghany, Pa. Capt. Sam Hague went to Ravenna last Tuesday to assist opening up at that town. Lieut. Will Embs expects to give his farewell in Akron next Sunday. This young man is well liked in the city and has made many warm friends, who will regret his departure. The Army expects to open up in Newark, O., Sunday.[7]

Furthermore, Hudson is known to have used other Salvation Army songs in his books. He used two songs by Army member Capt. Robert Johnson in Songs for the Ransomed (1887; repeated in Quartette, 1889), namely, “Marching on in the light of God” (1883) and “Soldiers of our God, arise” (1884), the latter without credit.

While the gospel refrain “At the cross, at the cross, where I first saw the light” was initially championed by the Salvation Army, it has now been embraced by lovers of gospel hymns across many denominations, languages, and nations, especially via the version by Hudson.

by CHRIS FENNER

with GORDON TAYLOR

and MARTIN WHYBROW

for Hymnology Archive

20 July 2021

rev. 2 August 2021

Footnotes:

“Governors Island’s Musical History,” Governors Island (11 Dec. 2020): https://www.govisland.com/blog/governors-islands-musical-history

N. Lee Orr, “John Hill Hewitt: Bard of the Confederacy,” The American Music Research Center Journal, vol. 4 (1994), p. 65. Orr puts Hewitt in Augusta during the latter part of the Civil War, 1862–1865.

“Herman L. Schreiner Dead,” The Morning News (Savannah, GA: 7 Sept. 1891), p. 8: PDF

“The Salvation Army: General Booth at Luton,” The Luton Reporter (28 April 1883), p. 8.

The Hicksville News (Hicksville, OH: 12 June 1884), p. 3.

The Summit County Beacon (Akron, OH: 2 July 1884), p. 1.

The Summit County Beacon (Akron, OH: 19 Nov. 1884), p. 4.

Related Resources:

William Reynolds, “Alas! and did my Saviour bleed,” Hymns of Our Faith: A Handbook for the Baptist Hymnal (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1964), pp. 5–7.

Ernest K. Emurian, “Take me home at the cross,” The Hymn, vol. 31, no. 3 (July 1980), p. 195: HathiTrust

Gordon Taylor, Companion to the Song Book of the Salvation Army (Atlanta: Salvation Army, 1990), pp. 113, 169, 216, 254–255, 339.

Carlton R. Young, “Alas! and did my Savior bleed,” Companion to the United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: Abingdon, 1993), pp. 187–189.

Robert Cottrill, “Today in 1837 / Today in 1901,” Wordwise Hymns (14 June 2010): https://wordwisehymns.com/2010/06/14/today-in-1837-william-c-dix-born/

“Alas! and did my Savior bleed,” Hymnary.org: https://hymnary.org/text/alas_and_did_my_savior_bleed