At the name of Jesus

altered as

In the name of Jesus

with

EVELYNS

PRINCETHORPE

CAMBERWELL

CUDDESDON

KINGS WESTON

I. Textual History

The passage in Philippians 2:5–11 known as the kenosis hymn or sometimes called the Great Reversal is regarded as an early Christian hymn in its own right, possibly predating Paul’s letter to the Philippians, possibly not written by him but something already in circulation he chose to record.

This early hymn became the seed of another magnificent hymn in praise of Christ written by Caroline Noel (1817–1877), daughter of Gerard T. Noel (1872–1851) and niece of Baptist W. Noel (1799–1873), both ministers in the Church of England, hymn writers, and hymnal compilers. A few of Caroline’s hymns were written as a teen, but most were written during the last 20 years of her life as her health wavered. John Julian wrote, “Miss Noel, in common with Miss Charlotte Elliott, was a great sufferer, and many of these verses were the outcome of her days of pain.”[1]

Noel, given her physical struggles, might have been drawn to the kenosis because of the way the Bible offers to uplift the humble. Her hymn “At the name of Jesus” was first published in the enlarged edition of The Name of Jesus and Other Verses (1870 | Fig. 1). The title of her book is based on the first hymn in the volume, “The Name of Jesus,” beginning “One Name alone in all this death-struck earth,” which is a compelling multi-stanza meditation on the name(s) of Jesus. Her most popular hymn, “At the Name of Jesus,” in contrast, is more about the redemptive work of Christ and the glory due to him in his position of heavenly kingship. In its original context, given in eight stanzas of eight lines, without music, it was labeled “Ascension Day,” an appropriate designation for Christ’s return to and eternal reign on the throne.

Fig. 1. The Name of Jesus and Other Verses for the Sick and Lonely, Enlarged Ed. (London: William Macintosh, 1870).

In the supplement to Julian’s Dictionary of Hymnology (1907), he reported, “In the 1903 ed. of Church Hys. this hymn by Miss Noel has been restored to its original reading, ‘In the name of Jesus,’ at the request of her family.”[2] This is quite likely in reference to the emergence of the Revised Version of the Bible, where Philippians 2:10 reads “in the name of Jesus,” versus the King James’ “at the name of Jesus.” Since the Revised Version was released in 1881, four years after Noel’s death, the change would have been motivated by her surviving family, not because this was Noel’s original wording, but because they felt it was more faithful to the original wording of the Greek, a slight misconception on Julian’s part. In spite of the family’s wishes, this version has not taken hold in the broader hymnal corpus.

Fig. 2. Church Hymns with Tunes (London: SPCK, 1903).

This printing illustrates the inconsistency of meter in Noel’s stanza beginning “Name Him, brothers, Name Him,” with iambic second and third lines. Here the editors made a musical accommodation; other hymnals make textual adjustments. For more on PRINCETHORPE, see below.

The editors of the enlarged edition of Songs of Praise (1931) added a doxology, “Glory then to Jesus,” which has been repeated in some other collections.

II. Textual Analysis

Regarding the kenosis hymn, Bert Polman noted an important function of the passage as an early creed, saying, “That early Christian credo quoted by Paul summarizes the essence of Christian beliefs about the incarnation, atoning death, exaltation, and return of Christ.”[3] Noel’s overarching structure somewhat reflects this general outline, adding Christ’s role in creation in her stanza 3, then briefly covering incarnation, death, and resurrection in stanza 4, the ascension in stanza 5, and the ultimate return in stanza 8.

The first six lines of the hymn are a clear appeal to the last part of the kenosis hymn, Philippians 2:9–11, with the last two lines picking up language from John 1:1. The text also harkens to Psalm 24:10 (“Who is the King of glory? The Lord of hosts, he is the King of glory!”). Literary scholar Anthony Esolen brought attention to Noel’s technique:

Notice that the name Jesus and the title mighty Word bracket the stanza: The two are one. That means that the adverb now, which ends the first half of the stanza, isn’t just tossed in to provide a rhyme with bow. Good poets don’t search for rhymes; they have them already, and use them for many purposes. Here the now of our time is placed in the context of the existence of the Word from the beginning.”[4]

Stanza 2 delves more into the nature of who Christ is and what he represents. The first four lines pull from the language of John 1:1–5, especially the ideas of Christ co-existing with God the Father, and Christ as light. The next two lines put Christ in the context of the Godhead with the Father and the Spirit. The last two point to Christ as a source of love (John 5:12–13, Eph. 5:2, etc.) and of rest (Matt. 11:28).

Stanza 3 begins resumes the narrative part of the hymn, carrying forward the presence of Christ “from the beginning,” looking to his role as creator. For this, Noel has again appealed to John 1, especially verses 3 and 10, but here she especially looks also to Colossians 1:16, “For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him” (ESV). Noel’s unique phrasing “thrones and dominations” comes from a literary tradition often credited to John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), lines 600–602, and repeated by others:

Hear all ye angels, progeny of light,

Thrones, dominations, princedoms, virtues, powers,

Hear my decree, which unrevok’d shall stand.

Nonetheless, some hymnal editors change “dominations” to something else, such as “bright dominions” to better reflect the more common biblical language.

Stanza 4 returns to the roots of the hymn in Philippians 2. Whereas the first stanza concentrates on the last part, his glorious kingship, this stanza deals with the humbling of Christ, his assumption of a human body, his bearing of our penalty, but also his victory over death. Some scholars have noted how the Scripture text says it was the Father who “bestowed on him the name that is above every name,” whereas Noel’s hymn says a name was received “from the lips of sinners.” Philippians 2 in particular assigns the name “Lord,” whereas Noel did not specify the name she had in mind. One name he received from sinners was “Christ” (or “Messiah”). Consider, for example, Mark 8:29 (“And he asked them, ‘But who do you say that I am?’ Peter answered him, ‘You are the Christ.’”) or Luke 23:39 (“One of the criminals who were hanged railed at him, saying, ‘Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!’”; see also John 1:41, 4:25).

The narrative continues in stanza 5, with his glorious ascension and seating on the throne (Mark 6:19, Luke 24:5-53, Acts 1:9–11). Here the “perfect rest” mentioned in stanza 2 is seen in its heavenly completion.

Much like her other poem, the namesake of her book, Noel used stanzas 4 through 6 to contextualize the spiritual narrative in terms of a name. Stanza 6 also marks a shift from narrative to application. Anthony Esolen described it this way:

Then Noel turns toward us. It’s a turn we will see again and again in the old hymns. Once the poet has meditated upon who God is, or upon what God has done, the lesson will be applied to us, in our troubled lives now. The stanzas are cast in the form of exhortation and command. … Consider the profound prayer it enjoins on us—the urgency of the repeated command underscores it. We are to name Him—with a catch in our breath, with wonder and reverential fear. The very name of Jesus is a prayer. We are to dwell upon it because of what He has done for us, but more because of who He is.[5]

In the sixth stanza, “love as strong as death” is a nod to Song of Solomon 8:6. The first part of stanza 7 possibly relates to Hebrews 4:16 (“Let us then with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need,” ESV). It also, in a sense, conveys the notion of Philippians 2:5, to put on the mind of Christ.

The final stanza pertains to the Second Coming (Matt. 24:30–31, Lk. 21:27, Acts 1:10–11, Rev. 19:11–16), coming in glory with a host of angels. The first line, with its “brothers,” as with the first line of stanza 6, is typically altered to “Christians,” especially since the 1980s. The fourth line, “With His angel train,” is often altered to read “O’er the earth to reign,” as in the Episcopal Hymnal 1940, or something similar. Hymnologist Carl Daw felt the fifth line was worth preserving, “because ‘all wreaths of empire’ is such a marvelous phrase, capturing as it does a detail of the historical period in which Christ was on earth yet also gaining a certain timelessness by its difference from the present day.”[6] Noel bookends the hymn, returning from where it started, with confessing the King of Glory.

III. Tunes

1. EVELYNS

Noel’s text has paired with a number of possible tunes. One of the earliest pairings still in use is the tune EVELYNS, written for this text by William Henry Monk (1823–1889) for the second edition of Hymns Ancient & Modern (1875 | Fig. 3). Erik Routley called this “one of Monk’s most successful tunes,”[7] and Kenneth Trickett said “It is a strong tune, capable of interpreting these words with great effectiveness.”[8] Monk’s setting includes a musical accommodation for the irregular iambic line, “With love as strong as death,” a curious decision considering the editors changed the following line, “But with awe and wonder” to conform to the meter. Nonetheless, Monk would not be the only composer to take a similar approach.

Fig. 3. Hymns Ancient & Modern, Rev. & Enl. (London: William Clowes & Sons, 1875).

2. PRINCETHORPE

In Church Hymns with Tunes (1903), as in Figure 2 above, the editors had used PRINCETHORPE, a tune by William Pitts (1829–1903), written when he was organist of the Brompton Oratory. This tune was first printed in Oratory Hymn Tunes (1871 | Fig. 4, pending), where it was called A DAILY HYMN TO MARY. Like Hymns Ancient & Modern (Fig. 3), the editors of Church Hymns opted to keep Noel’s irregular text and provide a musical accommodation.

3. CAMBERWELL

The tune CAMBERWELL was written for this text by John Michael Brierley (1932–) and published in Thirty 20th Century Hymn Tunes (1960 | Fig. 5) in a unison setting, the same year Brierley was ordained and became curate of Sourtport-on-Severn. A harmonized version was printed later in leaflet form, then both versions were included in the Methodist Hymns & Songs (1969 | Fig. 6) when Brierley was vicar of Dines Green. Notice how the first printing of the hymn tune in 1960 used the original first line, “At the name of Jesus,” but the Methodist printing used the alternate first line, “In the name of Jesus.”

Fig. 5. Thirty 20th Century Hymn Tunes (London: Josef Weinberger Ltd., ©1960), excerpt.

Fig. 6. Hymns & Songs (London: Methodist Publishing House, ©1969), excerpt.

In an errata sheet distributed with A Short Companion to Hymns & Songs (1969), editor John Wilson included this personal note from the composer:

I wrote the tune about 12 years ago [c. 1957]. I suppose it is really a march-like tune, to be played not too fast. It isn’t really like a lot of the other new tunes, as it has more of the traditional flavour, and can be played perfectly straight-forwardly, or, if necessary, it can be played with more freedom, as I often do. It is dedicated to Geoffrey Beaumont, and I called it CAMBERWELL as he was vicar of St. George’s, Camberwell, when I first met him.

4. CUDDESDON

When William Harold Ferguson (1874–1950) was co-editor of the Public School Hymn Book (1919), he included his composition CUDDESDON for Noel’s text (Fig. 7), and it also appeared with J.M. Neale’s text “Those eternal bowers man hath never trod.” Here the tune was marked “Anon” but it was credited to Ferguson in other collections. At the time, Ferguson was Warden of St. Edward’s School, Oxford. The tune is named for Cuddesdon Theological College, where the composer had studied in preparation for being ordained into the Church of England. In this case, the editors chose to revise Noel’s iambic lines, using “But with awe and wonder” from Hymns Ancient & Modern, and making the simple and sensible change at “With love strong as death.”

Fig. 7. Public School Hymn Book with Tunes (London: Novello, 1919).

5. KINGS WESTON

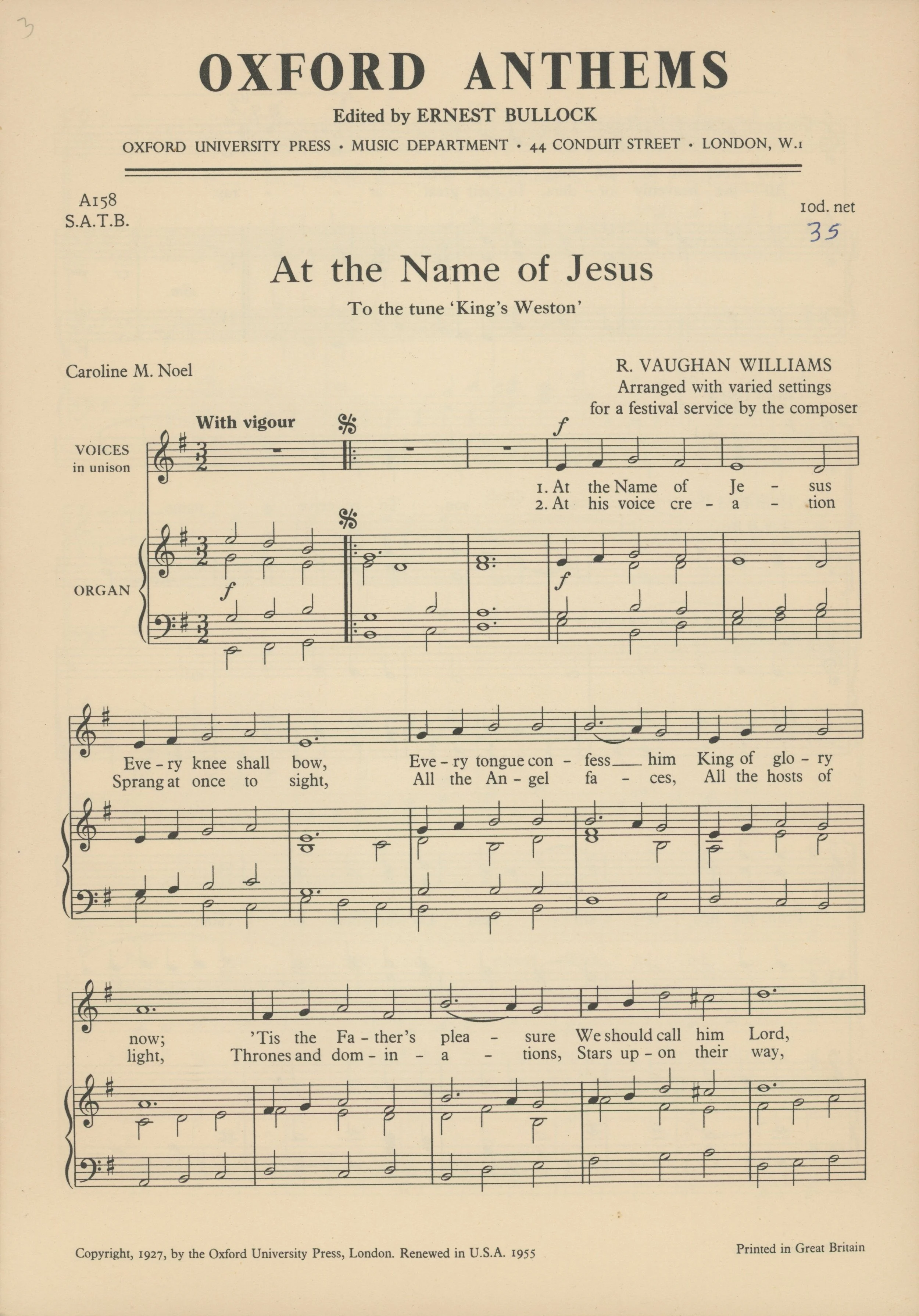

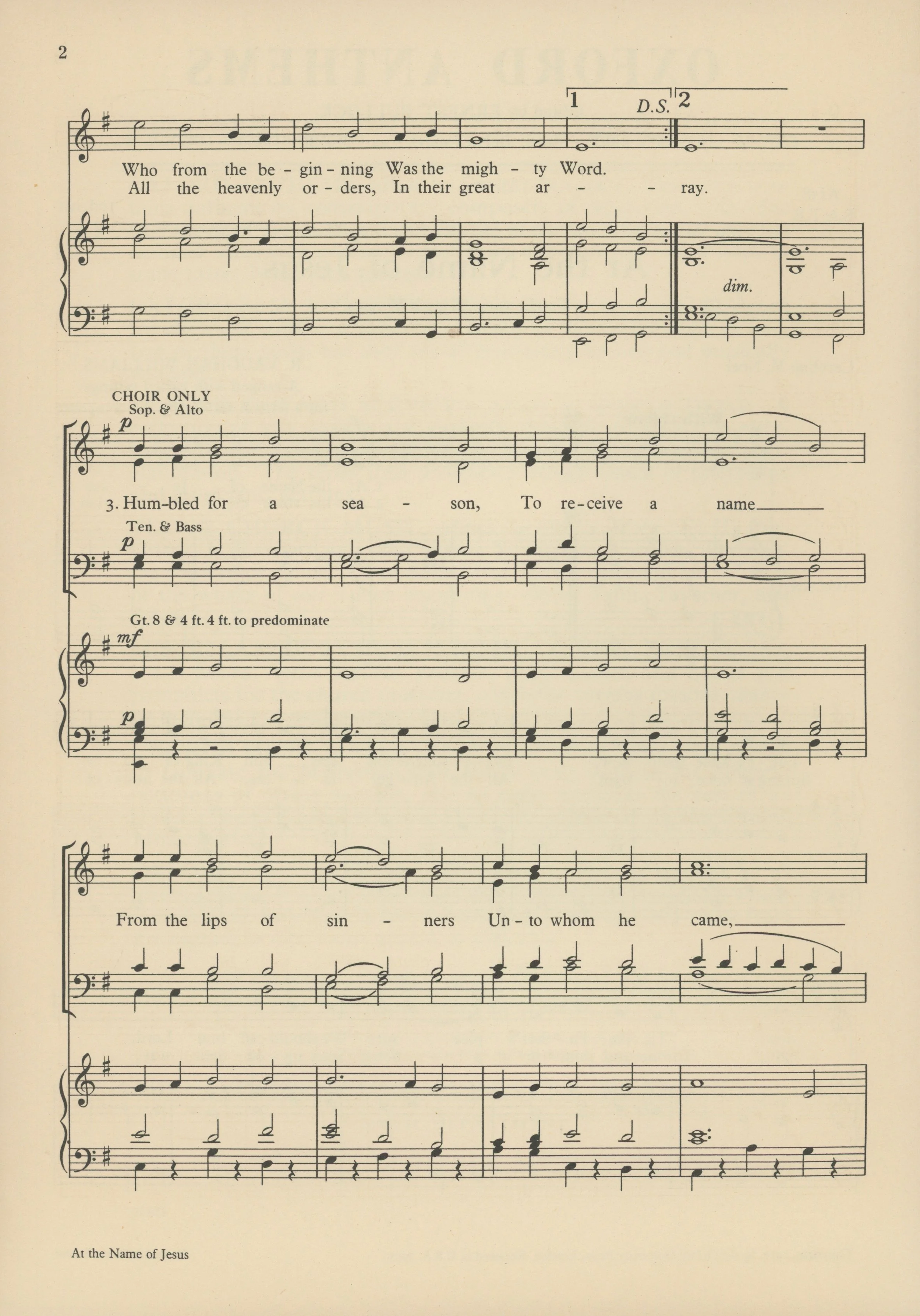

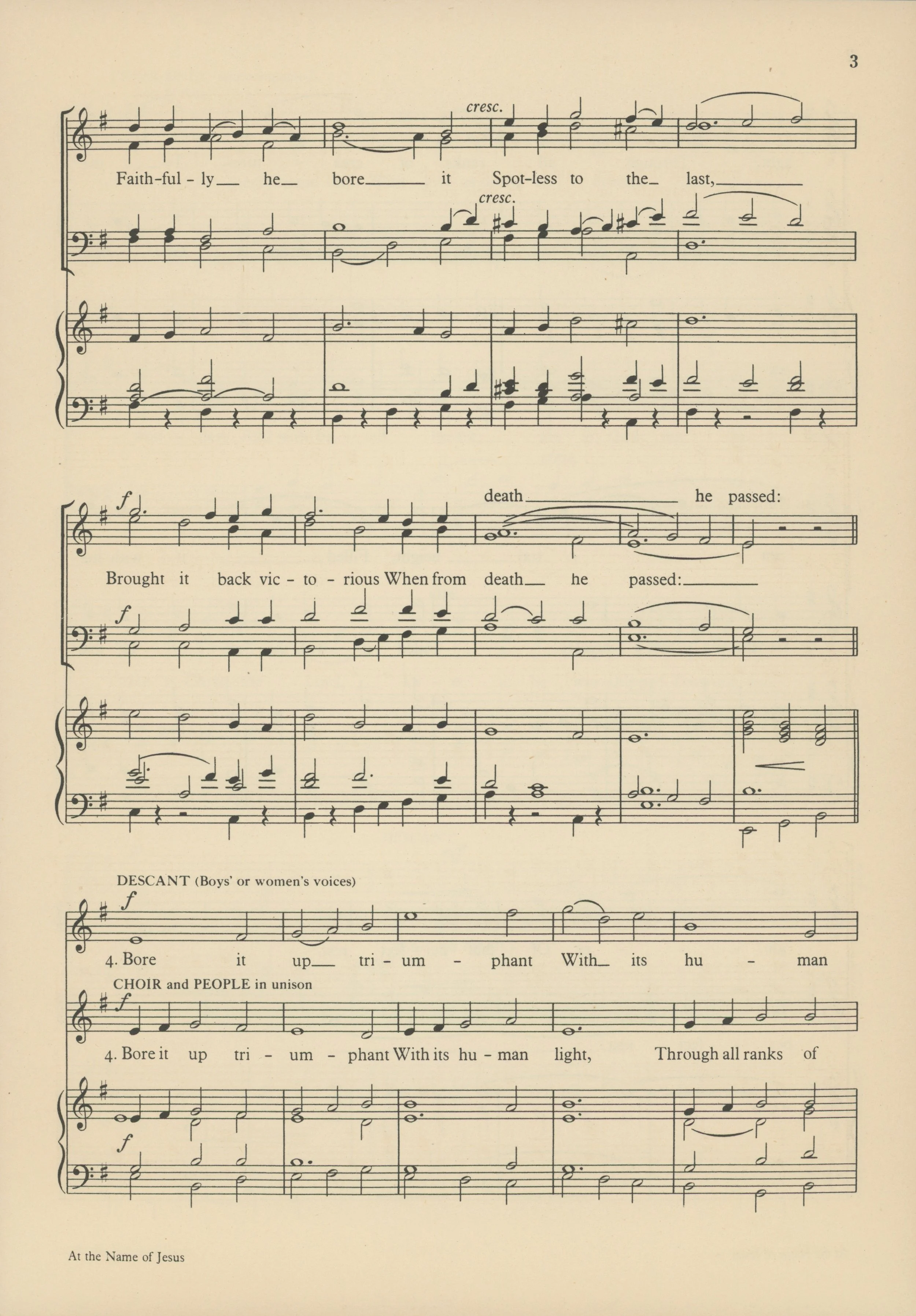

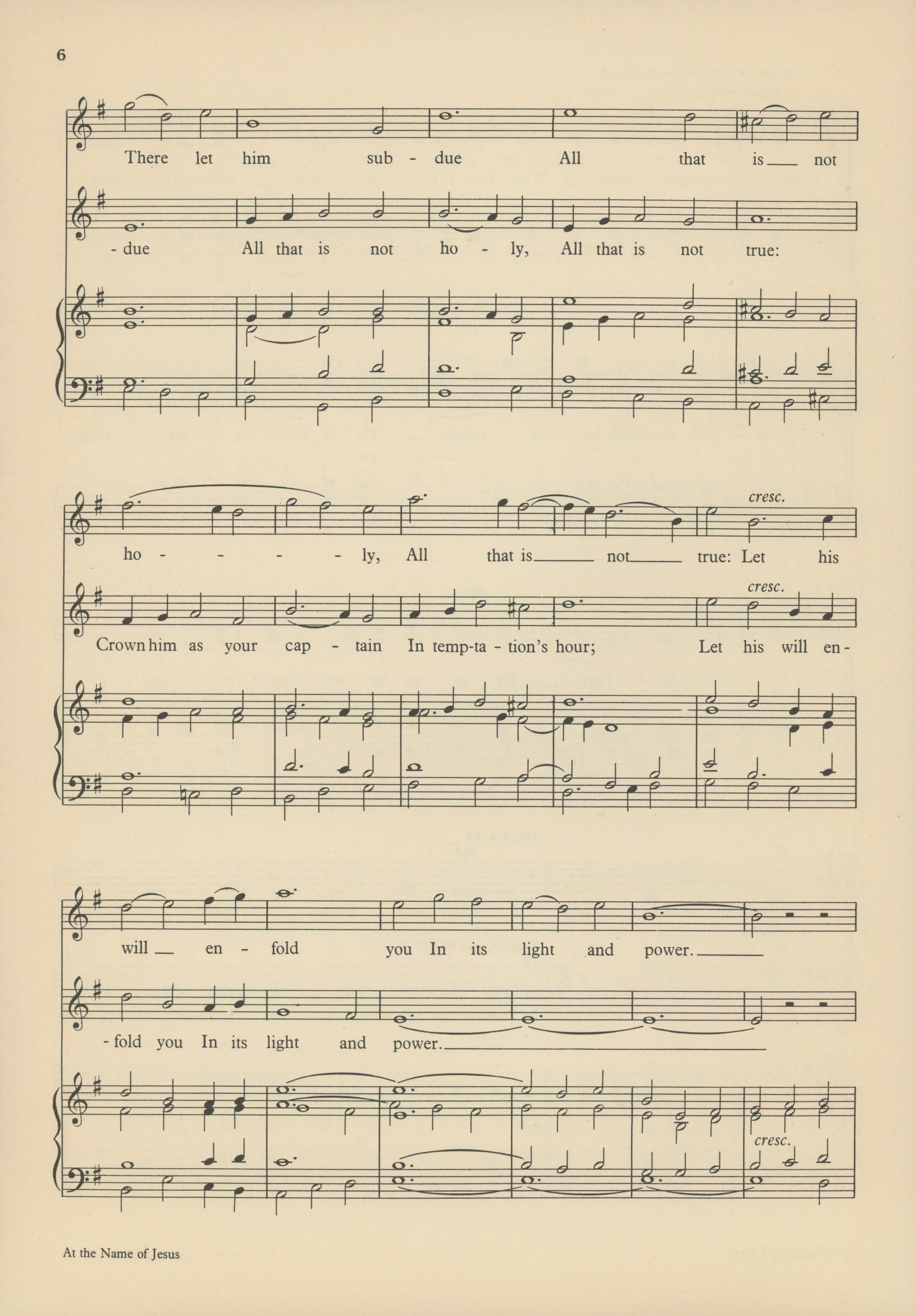

In 1906, when Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958) was editor of The English Hymnal (1906), he set Noel’s text to LAUS TIBI CHRISTE, a German processional tune, which dates as early as 1533 in a Schönenberg Nonnenkloster, possibly originating as a trope for the Kyrie. Apparently unsatisfied with this setting, Vaughn Williams composed his own tune, KINGS WESTON, for Songs of Praise (1925 | Fig. 8), a collection he co-edited. The tune is named after Kings Weston (no apostrophe), a historic estate on the Avon river in Bristol, England, where the composer had been a frequent guest.

Fig. 8. Songs of Praise (Oxford University Press, 1925), excerpt.

One of the tune’s most distinctive features is the consistent rhythmic pattern at the beginning of every phrase, which is inverted in the penultimate phrase. The melodic direction of that phrase is also inverted, descending rather than ascending like all the other phrases. This original printing included two musical accommodations, one in imitation of HA&M (Fig. 3), keeping “With love as strong as death” while incorporating “But with awe and wonder.” The other is a rhythmic adjustment to the end of the same stanza to avoid a having a long note on the word “and.” In the enlarged edition (1931), the editors instead avoided the musical changes by altering the text. That same edition introduced an apostrophe to the name (KING’S WESTON) and added the doxology “Glory then to Jesus.” Many other hymnals have repeated the faulty apostrophe.

In 1927, Vaughan Williams issued an anthem arrangement via Oxford University Press with choral harmonizations and a descant (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. “At the Name of Jesus” (Oxford University Press, 1927).

Vaughan Williams’ tune has become the most common tune setting for Noel’s text and has been widely praised. His colleague Archibald Jacob wrote:

It is a solid tune, in triple time, with a strongly stressed rhythm, and a characteristic exchange of accent in the last two lines; it is a dignified, but not a solemn tune, and must not be sung too slowly.[9]

Alan Luff added, “It is also unusual in being mainly harmonized in a sparse three-part texture.”[10] Reformed scholar Bert Polman said, “KING’S WESTON is a great tune marked by distinctive rhythmic structures and a soaring climax in the final two lines. Like many of Vaughan Williams’s tunes, it is best sung in unison with moderate accompaniment to support this vigorous melody.”[11]

Literary scholar Anthony Esolen, whose work deals mainly with texts, felt especially compelled to mention this tune setting in relation to Noel’s text; he remarked, “The brilliant and theologically sensitive composer of sacred music, Ralph Vaughan Williams, wrote a minor-key melody called KING’S WESTON for this hymn to bring out its power, especially in the climactic final lines of every stanza.”[12] Similarly, esteemed conductor-composer Alice Parker felt Vaughan Williams’ tune was crafted especially well to fit Noel’s text:

[The text] invokes majesty in its opening lines: we are to bow in the presence of this name. It builds, line by line, to the mighty Word at the conclusion of verse one. Always in the most dignified language, it tells of Jesus’s life, exhorting us to enthrone him, and crown him in our hearts, reaching an expansive climax in a vision of the Second Coming. This is High Church language: we are in a Cathedral, breadth and beauty lifting us to an exalted state.

Ralph Vaughan Williams . . . chose this poem for his tune KING'S WESTON (1925), and brought to life its majesty. He begins at the bottom of its modal scale and works its way upward, phrase by phrase, to the upper octave at the start of the last line. This large design reflects both the Cathedral and the huge scope of the poem. It is this slow building of tension in line after line that distinguishes both tune and text, reinforcing the richness conjured up by both components.[13]

by CHRIS FENNER

for Hymnology Archive

4 June 2020

rev. 4 January 2021

Footnotes:

John Julian, “Caroline Maria Noel,” A Dictionary of Hymnology with Suppl. (London: J. Murray, 1907), p. 1582: HathiTrust

John Julian, “At the name of Jesus,” A Dictionary of Hymnology with Suppl. (London: J. Murray, 1907), p. 1607: HathiTrust

Bert Polman, “At the name of Jesus,” The Hymn, vol. 43, no. 3 (July 1992), p. 39: HathiTrust

Anthony Esolen, Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books, 2016), p. 39.

Anthony Esolen, Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books, 2016), pp. 41–42.

Carl P. Daw Jr. “At the name of Jesus,” Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), p. 266.

Erik Routley, “EVELYNS,” Companion to Congregational Praise (London: Independent Press, 1953), p. 101.

Kenneth Trickett, “EVELYNS,” Companion to Hymns & Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing House, 1988), p. 76.

Archibald Jacob, “KING’S WESTON,” Songs of Praise Discussed (Oxford: University Press, 1933), p. 213.

Alan Luff, “KING’S WESTON,” The Hymnal 1982 Companion, vol. 3B (NY: Church Hymnal Corp., 1994), p. 818.

Bert Polman, “At the name of Jesus,” Psalter Hymnal Handbook (Grand Rapids: CRC, 1998), p. 633.

Anthony Esolen, Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books, 2016), p. 37.

Alice Parker, “Three times holy,” The Hymn, vol. 72, no. 3 (Summer 2021), p. 44.

Related Resources:

Percy Dearmer & Archibald Jacob, “At the name of Jesus,” Songs of Praise Discussed (Oxford: University Press, 1933), p. 213.

James T. Lightwood, “PRINCETHORPE,” The Music of the Methodist Hymn Book (London: Epworth Press, 1935), p. 503.

K.L. Parry & Erik Routley, “At the name of Jesus,” Companion to Congregational Praise (London: Independent Press, 1953), p. 101.

John Wilson, A Short Companion to Hymns & Songs (London: Methodist Church Music Society, 1969).

Stanley L. Osborne, “LAUS TIBI CHRISTE,” If Such Holy Song (Whitby, Ont.: Institute of Church Music, 1976), no. 462.

J.R. Watson & Kenneth Trickett, “At the name of Jesus,” Companion to Hymns & Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing House, 1988), pp. 76–77.

Mark Alan Filbert, “An analysis of ‘All praise to Thee, for Thou, O King divine’ and ‘At the name of Jesus’ in relation to Philippians 2:6-11,” The Hymn, vol. 40, no. 3 (July 1989), pp. 12–15: HathiTrust

Bert Polman, “At the name of Jesus,” The Hymn, vol. 43, no. 3 (July 1992), p. 39: HathiTrust

Carlton R. Young (with John Wilson), “At the name of Jesus,” Companion to the United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993), pp. 220–221.

Bert Polman, “At the name of Jesus,” Psalter Hymnal Handbook (Grand Rapids: CRC, 1998), p. 633.

Paul Westermeyer, “At the name of Jesus,” Hymnal Companion to Evangelical Lutheran Worship (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 2010), pp. 237–238.

Robert Cottrill, “At the name of Jesus,” Wordwise Hymns (10 May 2013): https://wordwisehymns.com/2013/05/10/at-the-name-of-jesus/

Anthony Esolen, Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books, 2016), pp. 37–43.

Carl P. Daw Jr. “At the name of Jesus,” Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2016), pp. 266–267.

Beverly Howard, “At the name of Jesus,” Sing with Understanding, 3rd ed., edited by C. Michael Hawn (Chicago: GIA, 2022), pp. 177–179.

Kenneth T. Kosche & Joseph Herl, “At the name of Jesus,” Lutheran Service Book Companion, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 2019), pp. 458–461.

“At the name of Jesus,” Hymnary.org:

https://hymnary.org/text/at_the_name_of_jesus_every_knee_noel